We Were Found: How Dear Evan Hansen Saved My Family

An editorial by FIM staff member, Ashley Poirier

During the five years that the original production of Dear Evan Hansen ran at the Music Box Theater in New York City (Dec. 2016 – Sept. 2022), cast members and creators received hundreds of letters from people who were touched by the story in a way no other musical had done before. From the benefit and detriment of social media to conversations about depression, addiction, suicide and trying to find your way – both as kids and as parents – in this new, tuned-in world, the show hit a lot of touchpoints that audiences otherwise were not sure how to discuss.

During the five years that the original production of Dear Evan Hansen ran at the Music Box Theater in New York City (Dec. 2016 – Sept. 2022), cast members and creators received hundreds of letters from people who were touched by the story in a way no other musical had done before. From the benefit and detriment of social media to conversations about depression, addiction, suicide and trying to find your way – both as kids and as parents – in this new, tuned-in world, the show hit a lot of touchpoints that audiences otherwise were not sure how to discuss.

My family and I were one of those audiences.

I lost my brother to an overdose in 2013. He had always been a troubled soul, so the grieving process was complicated. Of course, there was sadness, both in his death and in the life he had lived. There was anguish in the realization that the loss of my only sibling meant I had lost the only person who intimately understood my childhood.

But there was also relief in knowing he was at peace, and that those of us who survived him wouldn’t be called on to bail him out of another crisis. And that, as you can imagine, inspired guilt. Not to mention that my grieving process as his sister was different than that of my mom who had lost her child, and my dad – my brother’s stepdad – who felt it was his responsibility to care for his wife rather than process his grief.

But there was also relief in knowing he was at peace, and that those of us who survived him wouldn’t be called on to bail him out of another crisis. And that, as you can imagine, inspired guilt. Not to mention that my grieving process as his sister was different than that of my mom who had lost her child, and my dad – my brother’s stepdad – who felt it was his responsibility to care for his wife rather than process his grief.

All of these perplexing feelings resulted in general avoidance of the subject – and at times, of one another.

In 2019, on a whim, my dad whisked my mom, myself and my husband (at the time) off to Toronto to see a production of a musical he had never heard of: Dear Evan Hansen. As a proud musical theatre nut, I had memorized the Broadway cast recording top to bottom and was ecstatic about the opportunity to see it live (though it was a Mirvish production – not Broadway).

Even so, nothing could have emotionally prepared me for the experience.

The show runs the gamut in tone – from humorous to gut-wrenching – as it explores themes about family, community, and mental health. In particular, a family struggles with the recent suicide of their troubled teen son and brother. In the aftermath of his death, we see the family grapple with their own complicated feelings of grief: a mother clinging to new hope that her lonely child was actually a good friend; a stepfather wrestling with regret that he was never able to connect to the boy as a son; and a sister who, though tormented by her sibling in life, tries to remember him through the rose-colored glasses others seem to wear.

The show runs the gamut in tone – from humorous to gut-wrenching – as it explores themes about family, community, and mental health. In particular, a family struggles with the recent suicide of their troubled teen son and brother. In the aftermath of his death, we see the family grapple with their own complicated feelings of grief: a mother clinging to new hope that her lonely child was actually a good friend; a stepfather wrestling with regret that he was never able to connect to the boy as a son; and a sister who, though tormented by her sibling in life, tries to remember him through the rose-colored glasses others seem to wear.

Simultaneously we see Evan’s mother questioning how to raise her own lonely child, as well as a whole community coming together to give one another hope – albeit through some duplicity and misunderstanding.

When the finale came to a close in the Toronto performance – after Evan’s final letter promising to approach the world as the authentic self he is learning to love, and a hopeful message from the company that the sky’s the limit if you believe in yourself – my family and I found the catharsis we didn’t know we’d been craving since that dark spring of 2013.

We looked cautiously and knowingly at one another, eyes brimming with tears. We had seen ourselves on the stage. We were the family searching for answers, clinging to hope, wrestling with guilt and resentment and devastation. The family in the production had found words to express what we had been unable to. Moreover, they gave us permission to feel things we were uncomfortable acknowledging.

It is widely accepted, I think, that the arts can have a serious effect on mental health and emotional well-being. But just as we are all on unique journeys, each with a particular set of struggles, we all find resonance in different artforms.

A colleague of mine, Sawyer Auger, understands the unique power of music to connect. In addition to acting as Manager of Capitol Theatre Programming for FIM, he is also a singer/songwriter who uses his music to create spaces for conversations about mental health. He even collaborates with community mental health organizations in the towns he visits to generate maximum impact. “Music and art, in general, offer a unique and profound way to connect with people on an emotional level,” he told me. “They provide a safe space for expression and dialogue, which is crucial in breaking down the stigma surrounding mental health.”

Sawyer is open about his own mental health journey and insists that music was the key to walking through a door to healing. Much like my family’s breakthrough during our shared experience at the theatre, he finds peace in creating music and hopes that others find solidarity and perspective through his performances. “Through art, we can convey complex emotions and experiences in ways that words alone sometimes can’t, which makes it a powerful medium for promoting understanding, acceptance and support.”

For me, those profound connections have always come from musical theatre.

As a young person, while other kids were processing their emotions through heavy metal or wiping eyeliner-streaked faces after a good emo-sesh, I was blasting Les Miserables and Jesus Christ Superstar through my headphones. While my friends were raging over the release of Spice World: The Movie, I was playing the Hello, Dolly! film on repeat, determined to “hold my head up high … before the parade passes by!”

I was never the most popular kid in school, as you might have already surmised. But arts spaces and mediums have always been an inclusive haven for folks like me, who don’t feel like they “fit in.”

Sawyer even said that his personal experiences with music and mental health inform his approach to programming at FIM, where he hopes to “create events and opportunities that not only entertain but foster a sense of community and support.”

That’s why all of us FIMmers hang around, I think. Each of us has been touched by the arts in significant ways. We are passionate about the power of performance to change perspectives, build communities, heal spirits and bond families.

And we know firsthand that through engagement in music, lyrics, body movements, scripts and stories that resonate, folks find solidarity and a sense of belonging.

Or maybe, like my family, they find a way to express all that has gone unsaid.

The cast of Evan Hansen puts it this way: “There’s a place where you don’t have to feel unknown … And every time you call out, you’re a little less alone.”

That day in Toronto, my family and I lingered longer than most, content to sit in the space that had given us some emotional freedom, allowed us to silently connect through the shared experience, and for the first time in ages, feel a little less secluded by the grief we’d all felt the burden of bearing alone.

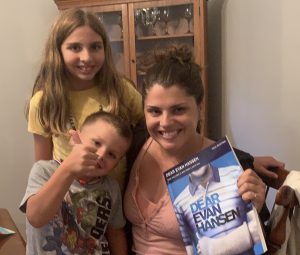

I have since shared the Dear Evan Hansen soundtrack (and the 2021 film) with my teenage daughter, who directly understands the pros and cons of growing up in a digital age, including its toll on her mental health and that of her peers. And she connects with the characters in the show as she navigates the new pressures that come along with the modern teen experience.

If you have ever had a teenager, you know they’re not always eager to communicate with their parents. But I am looking forward to experiencing the new production of Dear Evan Hansen with her at Whiting Auditorium in November, this time through the lens of a mother, wishing like Evan’s mom that there was a map to the uncharted waters of parenthood. And meanwhile hoping she feels, as I once did, that the show lives up to its promise: No matter how lost and alone you may feel, there is always someone who understands.

You will be found.

Dear Evan Hansen runs November 16 and 17 at FIM Whiting Auditorium. Tickets are available below or by calling the FIM Ticket Center at 810-237-7333.

Please bear in mind that the program discusses themes of suicide, drug use and bullying, and is best suited for audiences high school aged or older.